Long standing emphasis on architecture, which abounds with images of adorned individuals, has traditionally overshadowed the astonishing physical characteristics of the humans who built these magnificent cities and monuments to ancient civilization as well as to their gods and themselves. Body modifications served a purpose within their society that appeased their gods, rulers, and served an aesthetic purpose. These adornments were a social signifier of a person’s social status, with the rulers having a greater quantity of adornments, due to greater participation in rituals, as well as the highest quality jewelry. The Mayans pierced their bodies, not as we understand it today in the sense of adornment; rather they shed their blood in rites of sacrifice to their gods, or to keep the universe alive (Rush).

Mayan civilization reached its greatest florescence in the Classic period and was culturally, politically, and economically effected by developments in Central Mexico. Maya writings were meant as permanent records to proclaim genealogy, rituals and great deeds, and to legitimize rulers. The royal culture of Maya was that of political authority and quasi-divine status. Rule was based on a patriarchal lineage, with a rule of queens emerging only when a dynasty might otherwise be extinguished. Rulers were depicted sitting on jaguar skinned cushions, elaborate headdresses of jade, shell, mosaic, and plumage, holding a scepter carved into an image of K’awiil. Upon their deaths they were dressed, adorned, and accompanied by offerings. They believed that men and women were complementary opposites. The right side of the body is male, the left side is female, and an adult has to be married to be a whole person. The man plants and harvests while the woman cooks. A man also cannot hold a position without a wife to support him (Martin and Grube).

The classic Maya representations of the human body are unusually expressive, with a degree of naturalism that is deceptively transparent to western gaze. Classic Maya art is highly conventionalized and the western distinction between image and original collapses into shared identities and presences, involving effigies that both represent and are the things they portray. Attention to details of the body and clothing probably did not arise from the doctrine of shared identities, since these concepts pervade other more schematic representational styles of Mesoamerica, but they do indicate a strategy of depiction that emphasizes the recording of minute details, including those of faces and bodies in torment, lust and grief, and stresses close observation of an external world. These images provide sufficient raw material for understanding how certain passions were selected for display and what was meant by them (Houston).

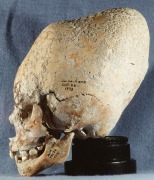

Before humans could significantly affect their environment, a great deal of effort was placed on the emphasis of the self. In addition to tattooing, scarification, skull binding and heavy dental alterations that include inlays and filing, ear, lip, and septum piercing was prevalent in most Mesoamerican cultures. The nearly universal process of ritualized adornment, traditionally enacted by elders or priests, permanently altered the flesh of the individual, and that healed tissue, which would later be enlarged to greater proportions contained within it jewelry. This jewelry and process of enlargement further defined the individual within his or her physical and spiritual world and within the cosmos and nature, and as an individual with in a tribe (Perlingieri).

Historically, most great civilizations were pierced, tattooed, or otherwise adorned in the fashion of their cultures. The aesthetic of the tribe was embodied in its kings and queens as well as the common citizens, as piercing is one of the most enduring human rituals, and jewelry making among the oldest human art forms. Much emphasis was focused around the ritual of a first piercing, which were often a rite of passage and a sign of beauty and tribal status. The piercing would necessitate the permanent modification of the body, as the process of enlarging the piercing required years to complete.

Ancient Maya men and women wore the same kinds of jewelry, except that women did not wear lip or nose plugs (Foster). The nose plugs were sanctioned for an elite status symbol among men, mainly during the Terminal Classic Period. The plugs, lip, nose and ear, were two-piece assemblages with a ring secured in the body by a thick plug. The earplugs were usually so heavy that they would distort the ear lobe, similar to modern ear plugs. These plugs were usually made from jade, semiprecious stones and shell. However, by the Early Post classic Period the jadeite resources were nearly used up, so turquoise and serpentine were used more frequently.

Certainly the Maya people did pierce their ears and other areas for adornment as well as for self-mortification. From the sculpture and wall paintings we can see they loved abundant and luxurious ornamentation. They practiced infant head shaping, eye crossing, and body paint. Noses, lips, septum, and ears were all pierced and adorned with expensive jewelry to show the wearer’s status. Genital mutilation is well documented and referred to in frequent visual metaphors (Christensen). Lips, noses, and earlobes were pierced and decorated with expensive jewelry. Body modification was also considered a badge of courage, as we deem it today.

Certainly the Maya people did pierce their ears and other areas for adornment as well as for self-mortification. From the sculpture and wall paintings we can see they loved abundant and luxurious ornamentation. They practiced infant head shaping, eye crossing, and body paint. Noses, lips, septum, and ears were all pierced and adorned with expensive jewelry to show the wearer’s status. Genital mutilation is well documented and referred to in frequent visual metaphors (Christensen). Lips, noses, and earlobes were pierced and decorated with expensive jewelry. Body modification was also considered a badge of courage, as we deem it today.

Ritualized as a child’s first ear piercing, a small human is physically indoctrinated by an elder in his or her tribe. It also functions as a “tribal baptism”; baptism and birth ritual is a reoccurring motif in many cultures. Any parent understands the natural impulse to dress, decorate, and raise your child in the style in which you and your tribe identify with, culturally. It is basic human instinct, genetically programmed for thousands of years culture is constant. Ritual rites of passage leave a mark like a piercing scar or tattoo. Within this context the individual is defined as a member within the animal world, the tribe, and the cosmos. Born without spots, stripes, or bright plumage, piercing and all ancient forms of body ornamentation is a uniquely human intervention; in fact it is a necessity (Perlingieri).

In Mayan societies, wood, bone, clay, or other more modest materials were employed by the peasant, or lower class. Graduated plugs were usual, but multiple twigs in the same hole were also used by those of limited means or as a sign of subjugation of those who had been stripped of rank. The relationship and symbiosis of adornment, culture, and ritual are inextricably woven (Perlingieri).

The Maya were master stone carvers who favored jade, jadeite, or nephrite, which symbolized fertility and harvest. They fashioned floral ear assemblages (Figure 2), some counter weighted, in endless variety. Gold symbolized the spirit world and the sun, and was the first and most enduring symbol of beauty and wealth in ancient culture. Both chronologically and geographically, many Mesoamerican civilizations traded goods and exchanged jewelry making techniques, information, and artisans. This is notable in the overlay and continuation of Olmec type imagery in Mayan art.

Nobles were entombed with their finest jewelry to accompany them into the afterlife. As civilizations complexities developed, classes emerged; kings and queens always embody their cultures particular style of personal finery. Nobility always wore the finest jewelry that could be constructed. The Mayans and other Mesoamerican cultures had a timeless fascination with gold and gem stones. Prominent awl-like needles often identified as sting ray spines, which are often found in tombs of buried Maya rulers in the pelvic area of male skeletons. Besides the needle sharp sting ray spines, excavators also discovered pointed blades of chipped flint and obsidian, awls of animal and human bone, as well as effigies made of precious jade. The central function of his duty and privilege of rank, by piercing his penis to bring forth the flow of “blue” blood, the Maya believed he sustained and nourished the land and its people. The triadic emblem of kingship common to the Maya area from earliest times contains as a central element, the upright spine of the sting ray. The “personified lancet” is thought to be an avatar of the deified flint knife, whose cutting edge is yet an aspect of the “smoking mirror” patron of princes and ruler of fate (Vale).

The sacrifice of the king is a theme which is recognized world-wide and is celebrated still in many cultures and many religions. The Mayan king’s blood had special powers to restore and nourish the land. The ruler and his nobles would pierce their tongues and genitals using obsidian knives, awls, and spines from the stingray or the maguey cactus, letting the blood drip into bowls set with paper blotters, which would then be ceremoniously burned as offerings (Figure 3). Sting ray spines were often found buried near the pelvic regions of male rulers.

Mayans offered sacrifices of their own blood, sometimes cutting themselves into pieces and leaving them in this way as a sign, other times they pierced their cheeks, and at other times their lower lips. Sometimes they scarify certain parts of their bodies, at others they pierced their tongues in a slanting direction from side to side and passed bits of straw through the holes with horrible suffering. They anointed the idol with blood which flowed from all these parts, and he who did this the most was considered the bravest, and their sons from the earliest age began to practice it.

Known to the Mayans rather prosaically as K’awiil and his association with the royal families in the late classic period seems to have been popularized by a dynasty at Palenque, which claimed certain congenital deformities as evidence of their divine kinship with this deity. The founder of this ruling family, Pakal, had inherited club foot which he likened to K’awiil’s snake foot.

Shield Jaguar, five days after he assumed the title of blood lord of Yaxchilan, performed the bloodletting rite, and is shown here supervising the tongue piercing ritual ceremony as it is performed by his principal wife lady Xoc (Figure 4). He wears a shrunken trophy head on his own and carries a staff which resembles the enormous tobacco smoking tubes used by warao on the orinoco today. Lady Xoc pulls a cord studded with maguey thrones through a hole in her tongue, the flaming designs of her mouth tattoo indicates the type of event her act is a part of, seeking a vision (Vale).

The Hero Twins, Hunahpu and Xbalanque, while on a hunting trip, shoot Vucub Caquix in the jaw with a blowgun, causing him to fall out of the tree he was sitting in eating fruit. Angered, Vucub Caquix tears off Hunahpu’s arm, and in order to recover the arm, the twins pose as dentists. They travel to Vucub Caquix’ house, and trick him into letting them pull his teeth to which they replace them with white maize kernels, while the arm is being retrieved. With his new corn dentures, Vucub Caquix no longer looked like a lord, so he died in poverty (Tedlock).

The corn cycle is intrinsically important to the Maya, beliefs about the spirit and nature of corn are paramount in their mythology. The Maya believe that corn has a spirit or soul, although how that essence is perceived or categorized varies slightly from region to region. they go to great lengths to ensure the spirit of the corn is not harmed, treating kernels of corn with respect, and holding every kernel in high esteem (Sweet). However, when Vucub Caquix was looked upon with his maize dentures he no longer appeared lordly because his teeth that had been painstakingly inlayed with precious stones were no longer part of his façade. The hero twins effectively stripped Vacub Caquix of his identity and title by merely removing his teeth. It is this stripping that diminished his status to that of poverty where he succumbed to death.

Continuing with ancient Maya jewelry, archaeologists have found evidence of teeth filing and inlays (Miller). All social classes of the Maya would file their teeth into points or other ornamental shapes. However, only the elite classes would drill holes in their teeth and place jade, hematite, turquoise or pyrite inlays in them. The Mayans had highly developed dental skills, not acquired for oral health or personal adornment but probably for ritual or religious purposes. They were able to place carved stone inlays into prepared cavities in live front teeth, in people’s mouths (Figure 5). A round, copper tube similar in shape to a drinking straw, was spun between the hands or in a rope drill, with slurry of powered quartz in water as the abrasive, cutting a round hole through the enamel. The stone inlay was ground to fit exactly into the cavity. These inlays were made of a variety of minerals of beautiful colors, including jadeite, iron pyrites, hematite, turquoise, quartz, serpentine and cinnabar . Like the act of tattooing, both filing and drilling were very painful.

A tattoo is more than a painting on skin, its meaning and reverberations cannot be comprehended without knowledge of the history and mythology of its bearer. Thus it is a pure poetic creation and is always more than meets the eye. As a tattoo is grounded on living skin, so its essence emotes poignancy unique to the mortal human condition. Piercing also underscored the difference between primitive humans and the animal world. It can also be stated that as the sophistication of jewelry making and the adornment process developed, so too did the complexity of a cultures concept and use of ritual, spirituality and the supernatural world, and ultimately religion (Vale).

Tattoos in ancient Maya culture were common in that both women and men had them, although men did not tattoo before marriage (Foster). The process of tattooing was fairly simple, although extremely painful. First, the intended design would be painted on the body. Then, the design would be cut into the flesh. The mixture of paint and the resulting scar would produce the tattoo. Getting a tattoo was a sign of great personal bravery because it usually caused an infection that resulted in interim illness. Tattoos were also used as a form of punishment; if a nobleman committed a crime; he was obliged to have his entire face tattooed as a representation of his crime.

In lintel 16 (Figure 6) a captured ruler is depicted on his knees and biting his fist in an act of submission in the presence of his captor, Bird Jaguar. There is a rope around his neck belaying the potential of him having been tied up. Normally rulers wear earspools of jade or other fine materials, but here he has been stripped of his finery and wears paper in his ear. Stripping captives of all their finery is an act of domination, it takes away their identity, clothing is important it identifies status, location, a number of things that leaves him more or less naked in front of his capturer. In a ritual context, paper is used to soak up the spilled blood so that it can be burned to nourish the patron deity of the performer.

It is possible that the men wanted to look like Pakal, who ruled the city of Palenque. Few ancient Maya remains have been as thoroughly studied as Pakal’s. His tomb within Palenque’s Temple of the Inscriptions provides a clear view of the standard of beauty to which ancient Maya men aspired. The earliest image of Pakal, a profile carving on an oval tablet found in his royal palace, emphasizes his flattened forehead. His simply rendered body reveals a slim physique. Pakal also had luxuriant hair, which he wore in thick, layered tresses trimmed to blunt ends in the front and tied in the back. His hair flopped forward like corn silk surrounded by leaves at the top of a healthy maize plant. Because each kernel on a cob requires a strand of silk to be pollinated, abundant corn silk pointed to a healthy cob of maize and Pakal’s hair indicated his maize like perfection.

Maya standards of beauty based on the Maize God applied to men as well as women. K’inich Janaab’ Pakal (Pakal the Great), is shown on the lid of his sarcophagus wearing the Maize God’s jade skirt. It is the same skirt his mother is shown wearing on an oval tablet from the royal palace at Palenque. Women’s skulls were also bound into elongated shapes, and they filed their teeth or drilled holes in them to hold inlays of jade, pyrite, hematite, or turquoise. Another fashion that men and women shared was painting their bodies with abstract designs (Miller).

It has been commonly established throughout the years that jewelry in the archaeological record is vastly important for many reasons, including giving archaeologists tangible evidence of what they see the ancient Maya wearing in depictions on murals or pottery and for ascertaining if trade existed between Maya cities or even other cultures, such as the Aztecs or some Caribbean cultures. When jewelry is found, it becomes possible for archaeologists to reconstruct a general image of what the ancient Maya wore in their daily lives, in religious ceremonies and in times of warfare. In addition, determining what materials the jewelry is made from, such as shell or jade, may help archaeologists clarify where the materials came from, giving hints about contact and trade. Since much of the jewelry the ancient Maya created does not degrade rapidly in the archaeological record, it will continue to be a source of much information for archaeologists.

Body modifications made by the Mayans were as much ritual as they were adornment, serving as visual signifiers of bravery and social class. From the current knowledge of Mayan societies, it is understood that bloodletting rituals were prevalent, cultural identity was linked to appearances, and their history was explained through mythology.Due to missionary contact and western encroachment in general, which includes the depletion of the environment, most tribes are disappearing along with what is left of their native rainforest. These things and the long arm of our righteous western morality have destroyed many primitive cultures and their mythologies (Perlingieri). The resources available for discerning Mayan myths and artifacts are limited, many of these have been tampered with, resulting in the original location being unknown. There have been innumerable leaps in understanding over the years, but there remains a lot left to learn about this culture.

Rush, John A, Spiritual Tattoo: A Cultural History of Tattooing, Piercing, Scarification, Branding & Implants, 2003

Martin, Simon, and Nikolai Grube. Chronicle of the Maya kings and queens: deciphering the

dynasties of the ancient Maya. London: Thames & Hudson, 2000. Print.

Houston , Stephen. “Decorous Bodies and Disordered Passions: Representations of Emotion among the Classic Maya.” World Archaeology 33.2 (2001): 206-219. JSTOR. Web. 4 Apr. 2013.

Perlingieri, Blake Andrew. A brief history of the evolution of body adornment in Western culture: ancient origins and today. United States: Tribalife Publications, 2003. Print.

Foster, Lynn V. Handbook to Life in the Ancient Maya World. 1st ed. 1. New York, New York: Oxford University Press, 2002. Print.

Christensen, Wes, “A Fashion for Ecstasy; Ancient Maya Body Modifications” in Vale and Juno, Modern Primitives, Re/Search Publications, 1989

Tedlock, Dennis. Popol vuh: the definitive edition of the Mayan book of the dawn of life and the glories of gods and kings. New York: Simon and Schuster, 1985. Print.

Sweet, Karen. Maya sacred geography and the creator deities. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 2008. Print.

Miller, Mary. “Extreme Makeover.” Archaeology. January 2009: 1. Web. 13 April 2013.

She began wearing a corset day and night to reduce her waist size. After several years the result was ethel’s legendary 13 inch waist, the smallest waist ever recorded on the 50’s institution The Guinness Book of Records. One cannot deny that William was one of the harshest task masters in the history of fashion. Ethel was a product of fashion and sexual fetish. Her husband believed that fashion influenced the structure of our most intimate thoughts. When William and Ethel married in 1928, she wore very high heels, beautiful earrings, and a short knee-length skirt. A corset completed her outfit. After the birth of their daughter Ethel’s breasts had become larger, like any man William was excited by this change, unfortunately this change did not last, and so he suggested wearing gold rings in her nipples, which she refused at first.

She began wearing a corset day and night to reduce her waist size. After several years the result was ethel’s legendary 13 inch waist, the smallest waist ever recorded on the 50’s institution The Guinness Book of Records. One cannot deny that William was one of the harshest task masters in the history of fashion. Ethel was a product of fashion and sexual fetish. Her husband believed that fashion influenced the structure of our most intimate thoughts. When William and Ethel married in 1928, she wore very high heels, beautiful earrings, and a short knee-length skirt. A corset completed her outfit. After the birth of their daughter Ethel’s breasts had become larger, like any man William was excited by this change, unfortunately this change did not last, and so he suggested wearing gold rings in her nipples, which she refused at first. In the Woman’s Sunday Mirror of June 16, 1967 Ethel was photographed wearing five inch heels and a black leather belt over her dress, she was now 52 years of age and a mother of a 27 year old daughter. Her final measurements were 36/13/38. Ethel had 12 piercings in each ear, eleven holes ran along the edge, and one was placed in the middle called a Conch. She also had each of her cheeks pierced, a Medusa and Laberate, both nipples, each side of her nose, and two piercings in her septum. William had stretched one of her septums, both nipples, conch, and lobe piercings. He had stretched her lobes so that daylight could be seen through, he was scared to go any further than 8mm due to the skin being so thin, and eventually he convinced her to stretch her nipples in an attempt to enlarge her breasts. At first she wasn’t comfortable wearing her jewlery and showing her figure off in public but after the war, with the change in fashion, Ethel and William began breaking down barriers. The septum rings she had worn in the privacy of their home for the pleasure of her husband was worn in public and she no longer hide the numerous piercings in her ears with her hair.

In the Woman’s Sunday Mirror of June 16, 1967 Ethel was photographed wearing five inch heels and a black leather belt over her dress, she was now 52 years of age and a mother of a 27 year old daughter. Her final measurements were 36/13/38. Ethel had 12 piercings in each ear, eleven holes ran along the edge, and one was placed in the middle called a Conch. She also had each of her cheeks pierced, a Medusa and Laberate, both nipples, each side of her nose, and two piercings in her septum. William had stretched one of her septums, both nipples, conch, and lobe piercings. He had stretched her lobes so that daylight could be seen through, he was scared to go any further than 8mm due to the skin being so thin, and eventually he convinced her to stretch her nipples in an attempt to enlarge her breasts. At first she wasn’t comfortable wearing her jewlery and showing her figure off in public but after the war, with the change in fashion, Ethel and William began breaking down barriers. The septum rings she had worn in the privacy of their home for the pleasure of her husband was worn in public and she no longer hide the numerous piercings in her ears with her hair.